Archaeologists in North Macedonia have uncovered the remains of a possibly long-lost ancient city far more ancient and important than previously known. Found near Crnobuki village, the Gradishte archaeological site was widely believed to have been a 3rd-century BCE Macedonian outpost in the time of King Philip V. However, recent discoveries by a collaborative research team of the National Institute and Museum–Bitola and California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt (Cal Poly Humboldt) have revealed a much deeper and richer history.

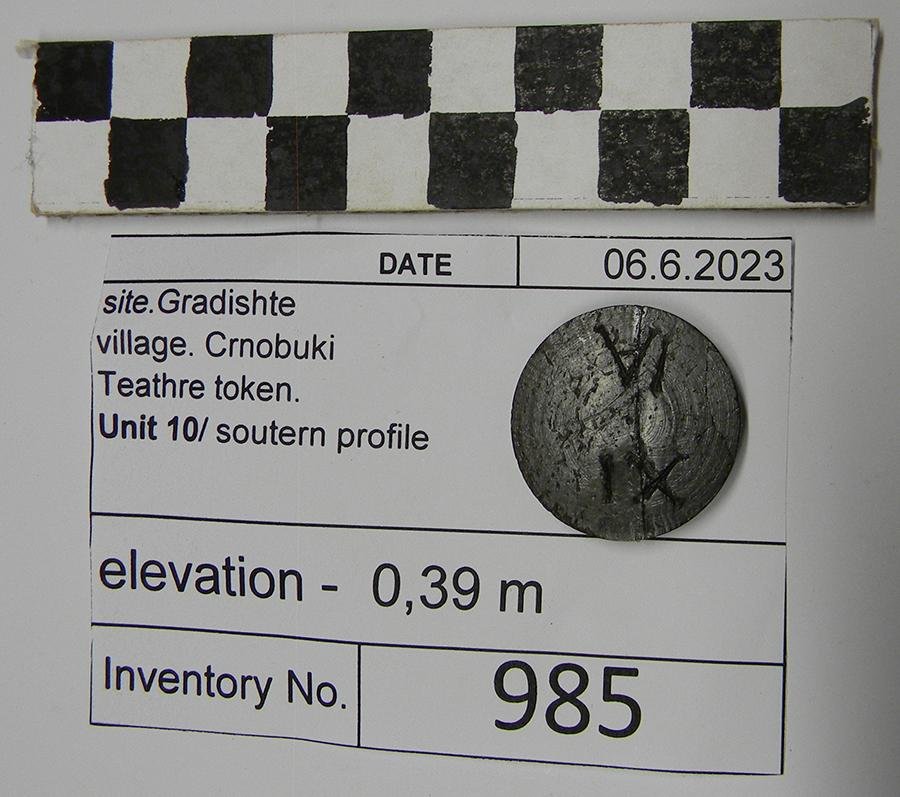

Using the assistance of modern technologies like ground-penetrating radar and LiDAR, researchers now believe the site could have been a vibrant urban center dating at least back to the Bronze Age (c. 3300–1200 BCE). Some of the most notable finds include stone axes, pottery fragments, game pieces, textile-working tools, and even a fragment of a clay theater ticket—items that suggest a rich, sophisticated society.

In 2023, the excavation took a thrilling turn when the team unearthed a coin that dates between 325 and 323 BCE, while Alexander the Great was alive. The discovery pushed the time period for peak activity at the site back to the period before, previously thought to have occurred during the reign of Philip V (221–179 BCE), by a century. Additional carbon dating of organic materials such as charcoal and bone has placed the site from circa 360 BCE to as recent as 670 CE.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime discovery,” said Nick Angeloff, an anthropology professor and archaeologist with Cal Poly Humboldt. “It highlights the complex networks and power structures of ancient Macedonia, especially given the city’s location along trade routes to Constantinople. It’s even possible that historical figures like Octavian and Agrippa passed through the area on their way to confront Cleopatra and Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium,” added Angeloff.

Angeloff and his team believe the location may be Lyncus, the ancient capital of the Kingdom of Lyncestis—an autonomous Macedonian kingdom that resisted conquest until conquered by Philip II, Alexander’s father, in the fourth century BCE. It may also be the birthplace of Queen Eurydice I, Alexander the Great’s grandmother, who was politically influential and a key figure in the early formation of the Macedonian state.

Engin Nasuh, curator-advisor archaeologist at the National Institute and Museum–Bitola, stressed the importance of the rediscovery of the site. He said, “We’re only beginning to scratch the surface of what we can learn about this period. I see it as a large mosaic, and our studies are just a few pebbles in that mosaic. With each subsequent study, a new pebble is placed, until one day we get the entire picture.”

Nasuh also pointed out that the Gradishte site was first mentioned in literature in 1966 but remained, for the most part, unexplored until modern times. Thanks to the College of Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences at Cal Poly Humboldt for providing funding, advanced tools have now revealed the city’s size, such as a seven-acre acropolis and what may be a Macedonian-style theater and textile workshop.

Rather than being a mere outpost, it appears the city was a focal point in Upper Macedonia that influenced trade, politics, and culture across the region. Through continuing excavations, the team of researchers is looking forward to uncovering even more information about the role this city played in the overall history of early European cultures and how they are connected to the rise of the ancient Macedonian state.

More information: Cal Poly Humboldt

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

Did anyone not realize that it would be useful and appropriate to either include the geographical location or provide a map for this interesting, incomplete finding?

Thank you for your comment. The exact location is sometimes withheld for various reasons, though the general area has been shared. If you’re a researcher and need precise location details for academic purposes, you may contact the responsible university for more details.

Wonderful, informative, a spectacular presentation.

Making history: I often wonder what will be left of our societies for future archeologists. Computer. Chips? Plastic products , data holders, computers, recordings of sorts. Or will they find the same artifacts as have been found, almost lasting forever, hewed from Stone .

K. Reeve